The Great Exhibition of 1851

A vision for Lunar Mission One

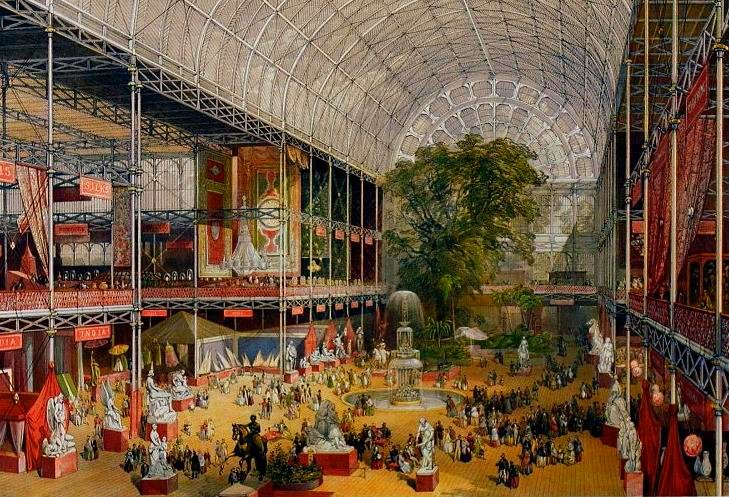

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was an international expo that took place in Hyde Park, London, from May to October 1851. Housed in the specially erected Crystal Palace, it was the finest exhibition of its time – a quintessential symbol of Victorian ambition. It ran for nearly five months, attracting six million people.

The Great Exhibition was not funded by the government or the wealthy elite of Britain, but by people of all classes contributing voluntarily. What followed was one of the greatest crowdsourcing projects in history.

Lacking Government funding to pay for the building, the Royal Commission, the body overseeing the event, set up over 300 local committees throughout the UK (Auerbach, Jeffrey A. The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display, Yale University Press, 1999). These committees were responsible for gathering the donations from their local communities. The UK public managed to raise £230,000 (around £28m or $45m today: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/education/Pages/resources/inflationtools/calculator/flash/default.aspx), with half the funding coming from pledges outside of London. In just 16 months, a site was chosen in Hyde Park, the iconic Crystal Palace (the largest covered structure on Earth at that time) was erected and 100,000 exhibits were assembled, ready to open to the public on 1 May 1851. The exhibits came from all around the World, created, delivered and installed freely for display.

The exhibition was a huge success, raising a surplus through admission fees of over £17m ($27m) in today’s money.

The exhibition was a huge success, raising a surplus through admission fees of over £17m ($27m) in today’s money.

When the Exhibition closed in October 1851, the Royal Commission was then re-established as a permanent body to spend the surplus to “increase the means of industrial education and extend the influence of science and art upon productive industry”. Indeed, the money was used to buy the land south of Hyde Park, and to help fund the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum – to this day three of London’s greatest educational attractions. The Royal Commission is also still active as a grant-giving educational trust. Each year it donates £2million ($3million) a year to support fellowships, scholarships and projects that promote to young people the opportunities presented by science and engineering.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 provides an inspirational example of how people can come together to build something extraordinary, and create a lasting legacy for generations to benefit from. These are among the core aims of Lunar Mission One.

Instead of choosing Hyde Park, we choose the Moon. Instead of building the Crystal Palace, we build a spacecraft. Instead of displaying exhibits, we record information. Instead of inviting people to pay for entry tickets, we invite people to pay to be part of the personal archive. Instead of celebrating the Industrial Age via the British Empire, we celebrate the Information Age via global space endeavor. |